A fantastic couple of weeks in a genuine tropical paradise. The crabs did everything that we were told that they would and more. It’s a really incredible behaviour and possibly unique to hermit crabs and humans. We certainly couldn’t think of another species which forms these ‘vacancy chains’ – individuals queue in order to move up from a limiting resource to a more suitable resource.

A fantastic couple of weeks in a genuine tropical paradise. The crabs did everything that we were told that they would and more. It’s a really incredible behaviour and possibly unique to hermit crabs and humans. We certainly couldn’t think of another species which forms these ‘vacancy chains’ – individuals queue in order to move up from a limiting resource to a more suitable resource.

Shells are everything in the world of the hermit crab, and an individual’s ability to grow is limited by the size of the shell it inhabits. Hermit crabs therefore rely on finding a shell slightly bigger and better than their own in order to move up the housing ladder. Sometimes these shells are occupied by another crab, sometimes not, and sometimes a small crab comes across an empty shell that is too big for it to move into. What’s really fascinating is that the crab then ‘knows’ that waiting next to the empty shell is a good strategy as, sooner or later, the presence of that big empty shell will probably set off a chain of ‘house moves’ that will result in an empty shell of a suitable size for it to move in to.

Within hours a large empty shell can have dozens of crabs patiently waiting next to it, sometimes arranged in neat lines according to size, all biding their time until the right sized crab turns up to unlock the chain – rather like the home owners on a housing ladder, waiting for the family at the top of the ladder to get their mortgage approved.

Sometimes this waiting is orderly, sometimes it disintegrates into a mass brawl, with multiple lines forming and tug-of-war battles developing between rival lines – while tiny crabs rush from the end of one queue to another trying to guess which line is going to win.

When the move finally happens the speed is incredible. Ten or more crabs can switch up in shell size in a matter of a few seconds, usually leaving a tiny empty shell at the end as everyone has moved up one size. Occasionally the chain would break down as an individual would move up in shell size but be reluctant to let go of his/her old shell and you’ll end up with a nude crab charging around desperately trying to figure out what to do, like the looser in a game of musical chairs. It was great behaviour but surprisingly tricky to film – small and sensitive creatures and a behaviour that can go from nothing to completion in a few seconds, but I think we got a really strong sequence.

We were lucky to be on the island with the nicest bunch of people you could imagine, Randi Rotjan (who discovered the synchronous vacancy chain behaviour) was absolutely fantastic, a brilliant advisor and great fun to work with.

The island was so lovely to work on; you wake up at sunrise, pull on swimming shorts, get some coffee brewing, and could be filming within 5 minutes. In addition to the very cool hermit crabs there were pelicans, a pair of ospreys, frigate birds and the bath-warm sea was filled with fantastic marine life.

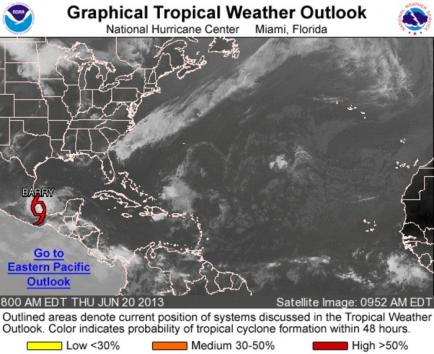

We got the bulk of the sequence filmed in the first 10 days, which was a good thing as the weather gradually deteriorated to the point that we found ourselves in the midst of the terrifyingly named Hurricane Barry. This resulted in 3 days of intense rain (7.5 inches one night), gale force winds, and huge seas – which somewhat re-moddeled the island. All the crabs climbed the palm trees which was very interesting, a bit unnerving (what did they know that we didn’t?), and behaviour which, in the future, I’ll take more seriously.

While I was away Max won U8 ‘Player of the Year’ and ‘Players Player of the Year’ at Witney Rugby Club – really well deserved.

There were lots of lovely things to photograph on Carrie Bow Cay, I became rather obsessed with taking pictures of the outhouse, which may herald an exciting new direction for my career ….

I’m off to Alaska for the 4th and final time of the year. This time for the BBC Natural History Unit’s Survival series.

I’m off to Alaska for the 4th and final time of the year. This time for the BBC Natural History Unit’s Survival series.